The Trojan solved the Bhima Koregaon case!

How proper file, malware, and memory forensics techniques were able to catch the ModifiedElephant threat actor planting incriminating evidence on defendants' computers in India.

Disclaimer: The views, methods, and opinions expressed at Anchored Narratives are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect my employer’s official policy or position.

Introduction

I agreed in late 2022 to independently review a new digital forensics report from Arsenal Consulting (hereafter: Arsenal), which was still under embargo. Niha Masih, an award-winning reporter with The Washington Post, reached out to me in early December and explained that she had written a series of articles (based on Arsenal reports) about Indian activists in the “Bhima Koregaon” case who were hacked and had evidence planted on their devices before their arrests. Niha asked if I would be able to validate Arsenal's work.

The new report from Arsenal (Report V) involved the examination of a forensic image (copy) of the hard drive of one of the defendants, Mr. Stanislaus Lourduswamy (hereafter: Swamy). The 84-year Jesuit priest, unfortunately, died in 2021 while still in the custody of Indian authorities.

The digital forensics report involved a lot of technical details on how information was reconstructed during Arsenal’s investigation, which included memory artifacts that were recovered from the hibernation file (hiberfil.sys) of Mr. Swamy's computer. As the report contained many technical details regarding memory forensic artifacts, which are not commonly investigated in this type of legal case involving digital forensics, my involvement made sense as I investigate memory images in my full-time job at Volexity.

Hibernation files usually contain a wealth of information but are basically the compressed contents of Windows memory from when the system goes to sleep. So, hibernation will preserve the last state of the computer. Usually, these files contain information about active processes but also network connections. Once the user resumes the computer, you can continue exactly where you left off. These files can be thoroughly investigated with the open-source memory forensic framework Volatility or Volexity's next-generation memory forensic Volcano platform.

After obtaining internal support (Volexity) for the review, I received the report produced by Arsenal from Niha the same day. After the review of the report was done, I also received several pictures from her of documents which included the official investigative questions (HDD Questionnaire) raised by the lead Pune Police officer and the official report from the Regional Forensic Science Laboratory (RFSL) in Pune relating to the digital forensic investigation into Mr. Rona Wilson. Mr. Wilson is another defendant in the Bhima Koregaon case. These court documents have not been included in the Arsenal reports or reported on by The Washington Post. In the RFSL report, I discovered something interesting – malware, not identified as such in the report, on an external pen drive that was seized from Mr. Wilson.

The Washington Post published its report covering Report V on 13 December 2022. On the same day, Wired Magazine reporter, Andy Greenberg, released another story.

In this anchored narrative (AN), I will outline some fascinating artifacts that were retrieved from artifact-rich files on the hard drive of Mr. Swamy by Arsenal Consulting. After that, I will detail the investigative questions raised by the Pune Police officer, the results produced by the RFSL in Pune, and the serious concerns I have with them. While examining their forensic lab report, I detected a piece of malware called H-Worm or NJRAT, which appears to be unrelated to the attacker who specifically targeted the Bhima Koregaon defendants. Still, it highlights that there were indications of malware in plain sight on devices seized from Mr. Wilson during the police investigation back in 2018! After that, I will address some risks with performing digital forensics at scale and the quality needed to perform these types of digital forensics investigations. Finally, I'll finalize this anchored narrative with recommendations and a conclusion.

Report V Swamy

Arsenal details its findings in its latest report, which can be read on the website of The Washington Post. This report provides detailed insights into how relevant artifacts were recovered and that the same findings should be able to be reproduced by any other digital forensic investigator with access to the forensic copy of the hard drive.

I will not go into every detail of the report as the findings stand independently. However, I want to highlight some things that should be really interesting to you about the memory forensic artifacts that the NetWire remote access trojan has left on the system of Mr. Swamy and the approach Arsenal took to recover relevant evidence.

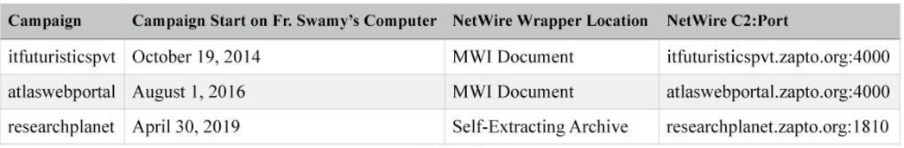

First, the Swamy evidence is linked in some ways to the other digital forensics reports (1,2,3,4) from Arsenal and demonstrates that multiple long-lasting spying NetWire campaigns started in October 2014. The campaigns identified by Arsenal push NetWire malware (among other things) to the compromised host(s).

Most of the indicators of compromise (IOC) associated with the malware found on the Swamy system can be found on VirusTotal and BFK. According to SentinelOne (S1), these IOCs relate to the threat actor group ModifiedElephant, and the group has been operating and targeting human rights defenders, academics, and lawyers since 2012. The group also targeted many other victims not related to this case, demonstrating the sheer size of the operation.

The NetWire software can be obtained from a 'dodgy' website and has been used by many threat actors in the past. The incident response team of Luxembourg published their technical analysis on two samples in 2014, which can be read here.

Many solid artifacts of the threat actor’s presence were found in Volume Shadow Copies (VSS), unallocated space, hibernation, and the page file of the hard drive of Swamy.

One of the more interesting artifacts in the Swamy report is the reconstruction of network traffic with the threat actor’s command-and-control servers (C2). From a forensic perspective, Arsenal follows an exciting approach leveraged in memory forensics quite often, but here with a twist. They first extracted slack space from the hibernation file of Swamy's system with their own forensic tool Hibernation Recon. Then they used the bulk_extractor tool made by Simson Garfinkel to scan the recovered slack and hibernation files for those network packets. This search resulted in recovered network activity, as seen in the screenshot below.

Arsenal also found remnants of NetWire’s “File Explorer” functionality within the unallocated space of Mr. Swamy’s computer. The File Explorer function allows the operator(s) of the NetWire tool to browse the file system of a person who is infected with the malware. However, the usage of this capability produced unique artifacts on the file system of Mr. Swamy. Especially in the computer's internal memory, the usage produced a distinct structure. Arsenal recovered many of those relevant artifacts from the file system of Mr. Swamy’s computer. Two of these relevant artifacts were recovered from the page file (swap) and unallocated space where the operator was viewing the hidden "mydata" folder contents before and after the delivery of two planted documents, which is displayed in the screenshot below.

In their report, Arsenal explains how they have obtained artifacts and how they have extensively modeled different NetWire versions’ behavior on disk, memory, and network in their lab environment. This reproduction process could only have been done by obtaining NetWire. This research is an essential part of digital forensics, giving them insight into how NetWire behaves and the artifacts it leaves behind. One of the benefits of extensive modeling was that Arsenal could reconstruct NetWire stacks from memory that ended up on Mr. Swamy’s disk. The two images below highlight two particular portions of a reconstructed NetWire stack and reveal some of the NetWire operator’s activities.

Appendix C of the Swamy report explains Arsenal’s modeling process. The screenshots below show what happens when similar activity (a NetWire file upload and directory browse) occurs in their testing environment.

In their report, Arsenal states that they will publish more detailed research into NetWire in 2023, which will give other researchers insight into Arsenal’s analysis methods and the opportunity to detect NetWire activity in other cases.

Investigative questions Pune Police evidence from Mr. Rona Wilson

As mentioned in the introduction, I received 24 pictures of the reports by the Pune police (11) and the RFSL (13) in Pune from The Washington Post reporter, Niha Masih. These reports describe evidence found on devices seized from Mr. Wilson. This section will outline the method of questioning by the investigator raised to the RFSL. My insight is limited as I do not have access to all the documents in this case. For brevity, only relevant sections in the pictures I was sent are highlighted with some screenshots below, and some are not, as they will identify people in Law Enforcement (LE). That is not the purpose of writing this Anchored Narrative (AN).

In the screenshot above, it appears the investigators raise relevant questions in the case against Mr. R. Wilson by filling in a report called “Questionnaire for HDD” which is then shared with the forensic lab.

In total, 26 questions were raised by the Pune Police investigation team. The last question, 26 was, “Please provide any other important facts or data of importance in view of evidence.” I’m not entirely sure how to read this question, but it seems like a bit of a failsafe to report any other information that does not align with the evidence. Unfortunately, I could not include a screenshot of that report as that would identify the lead investigator of the Pune Police. After reviewing these questions from a digital forensic perspective, it seems that the tactical investigation team is driving the digital forensic investigation by the RFSL and reviewing the collected or reviewed material. This is not an uncommon process, as tactical investigators usually have more insights into ongoing or long-lasting investigations. That said, tactical investigators should never be in the driving seat of the digital forensic process and reporting as they do not have the expertise to interpret the value of artifacts. I have many more remarks to make, but let’s review the report by the RFSL first.

Responses Regional Forensics Science Laboratory in Pune

The RFSL report in Pune was sent to me in a series of 13 pictures. Only relevant pictures will be shared.

All evidence was labeled with a certain exhibit number on 20 April 2018, as seen in the screenshot above. The forensic report also states which software has been used to perform the forensic acquisition of hard drives, DVDs, or pen drives and which hashes have been generated by the forensic EnCase software from Guidance Software (now: OpenText). Also, the forensic tool Cellebrite was used to examine the seized Hotspot and SIM cards.

In the screenshot above, details regarding Mr. Wilson’s hard drive are displayed, which include the operating system (Windows 7 Ultimate) and which deleted data, internet history, and relevant extracted files have been recovered or extracted from the file system(s) as requested by the Pune Police questions shown earlier.

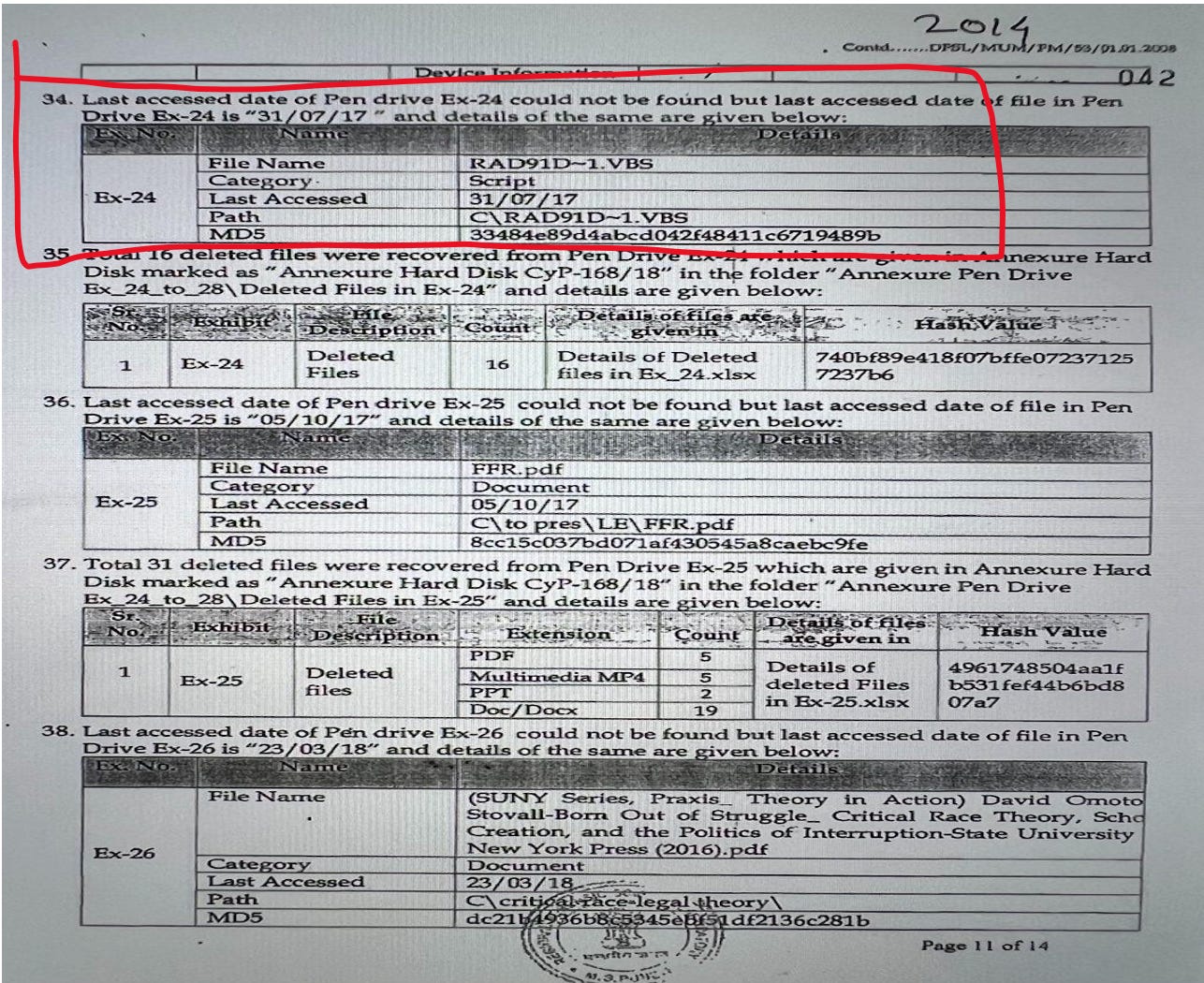

On page 11, point 34 of the Regional Forensic Science Laboratory report describes one of the most exciting aspects of their report. Namely, the mention of a Visual Basic Script (vbs) file, named “RAD91D~1.VBS” found on one of the pen drives seized from Mr. Wilson with a specific MD5 value (33484e89d4abcd042f48411c6719489b). According to the report of the forensic analyst of the RFSL, the last date of the “Pen drive Ex-24 could not be found but last access data of file in Pen Drive is 31/07/17”.The forensic analyst does not report anything strange about this file. As I noticed this peculiar file, I wondered what use Mr. Wilson, an activist but also public relations secretary of the Committee for Release of Political Prisoners, would have for a Visual Basic Script (vbs) file? The answer came quickly by looking up the MD5 value in VirusTotal, and the exact same file was found here. Some contents of the file can be seen in the screenshot below.

Although over 35 known anti-virus engines well detect the malware, not much additional information about its functionality or potential command and control servers is known on VirusTotal. However, some contents can be seen in the screenshot below after downloading the file.

As you can see, the malware contains a variable called "sufrete," which holds values separated by the word "arasadelomasco". On the right side of the screenshot, you can see how often that is repeated in the file. The obfuscated section in the script can be de-obfuscated by replacing "executeglobal lopeirt" by "WScript.Echo lopeirt" on line 291 of the vbs script. After that replacement, you will print the entire obfuscated content that is stored in variable lopeirt, and it reveals the well-known H-Worm, Houdini, or NjRat. You can find more on this simple Remote Access Trojan (RAT) on Malpedia. According to Malpedia, Mandiant wrote the first public report on H-Worm in 2013.

By examining the configuration of the malicious script, it became clear that the malware would propagate to USB drives if they were connected to the infected system. This malware version would receive its instructions from the C2 server with the hostname "wiredmax.no-ip.org" and communicate over TCP port 19004. Once a computer system is infected, the operator of the C2 server has access to the system with the rights the user has on the computer system.

So, to summarize, the Regional Forensic Science Lab reported on a piece of malware called H-Worm that was present on one of the pen drives seized from Mr. Wilson without mentioning that it was actually malware. Their report only mentioned the script's last access date, which was 31 July 2017.

On VirusTotal, you can also determine when the file was first uploaded and how good the anti-virus detection rates were at the time of the examination by the Regional Forensic Lab in Pune on 20 April 2018. Coverage of the malware during that period is displayed in the screenshot below.

So around 30 known anti-virus scanners would have detected this around the time of the arrest of Mr. Wilson. Every digital forensic specialist in 2018 should have known about malware on devices seized from suspects. So why was this not reported by the RFSL in Pune in 2018? Is it because the Pune Police did not ask such a question? Based on their own lab report, it does not seem to be a default process to perform an anti-virus scan on seized read-only digital device material or carved or recovered files. More importantly, the questions and responses seen by Anchored Narratives seem to defy basic digital forensic science principles to answer basic questions about who produced these artifacts.

So, what does this H-worm finding mean for the findings in Arsenal Consulting’s reports related to Mr. Wilson? Nothing really, as Arsenal's reports in terms of malware are focused on the attacker who performed surveillance and incriminating document deliveries against multiple defendants in the Bhima Koregaon case and does not describe unrelated malware. The H-worm malware detection is only an indication that malware should have been detected in RFSL processes, as their report mentioned the file in a vague way. The H-Worm operators used a different attack infrastructure than the attacker described in the Arsenal reports. I do not know if the pen drive in question was ever attached to Mr. Wilson’s computer, so the H-worm finding is interesting but irrelevant to the NetWire actor targeting Bhima Koregaon defendants.

Potential Risks in digital forensics at scale

Digital forensic processes have changed over the past ten years. Traditional detectives understand that most of their evidence in cases is produced by material from computers or smart devices. The trend I have seen grow is that the digital forensic process accommodates access to these traditional detectives by allowing them to search through searchable data or data that the digital forensic specialist has exported. The problem with this approach is that while in many of these cases, just exporting files and letting them be reviewed by tactical investigators is usually enough to solve a crime, in more complicated cases, relevant artifacts may be missed or misinterpreted. It appears that the digital forensic process is being done at scale in Pune, which lowers the quality of the digital forensic findings.

Based on the police and forensic lab questions and answers related to Mr. Wilson’s devices, you can see some of the following issues:

Data gets exported based on some parameters supplied by the investigation team. Are they the experts?

Is the exported data viewable by an investigator? In many cases, recovered files are broken and not viewable with common programs present on the computer.

Is the method of exporting data precise enough? In the case of Mr. Wilson, data was recovered with EnCase, which is not the most accurate way of recovering or carving deleted data. Better carving technology exists, for example, with PhotoRec, as those applications check for the file format of recovered data. EnCase usually uses a simple header/footer recovery approach, which is more error-prone.

Does the RFSL perform default anti-virus on all seized read-only or recovered data? At least it is not included in the report of Mr. Wilson or mentioned anywhere. Anti-virus scanning often gives a good indication of whether seized material could have been compromised.

As the majority of Mr. Wilson and Mr. Swamy's crucial findings come from Volume Shadow Copies, Hibernation or page files, or unallocated space, it does not seem that solid forensic practices have been used to identify relevant artifacts on the seized drives by the RFSL analysts in Pune.

Is there a feedback loop between the investigation team and the digital forensic scientists at the laboratory and vice versa?

Digital forensic scientists are the experts and need to safeguard the process in which they do their own analysis and reporting based on what has been seized by the investigation team. The forensic scientists, in this case, did not explain where relevant documents came from, where it is good digital forensic practice to determine which application, process, or user-created the relevant documents.

Recommendations

There are guidelines from Interpol and SWGDE and best practices on performing digital forensics, which can be found here and here. After reviewing these guidelines, I believe there is room for improvement within them in terms of embedding default anti-virus scanning and different investigative scenarios. Ultimately, these improvements will increase the quality of digital forensics and detect rogue operators that are incriminating illiterate computer users. But more importantly, the tactical investigator should never oversee digital forensic analysis and reporting as they are not experts in digital forensics.

So how good is your digital forensic process currently? Would you have detected not only the presence of NetWire, but also that it was used to plant incriminating documents, using your current digital forensics process? Maybe this is an opportunity to perform an annual red team exercise to determine the quality of your digital forensic process. For example, would you be able to detect a CobaltStrike or NightHawk operator who inserts some documents into a computer? Start testing!

Conclusion and concerns

In this anchored narrative, I have tried to highlight why Arsenal’s latest report provides excellent insights into how high-quality digital forensics should be performed for the digital forensic community. They leveraged all relevant and artifact-rich files (pagefile, hibernation file, volume shadow copies, slack and unallocated space) to reconstruct how the ModifiedElephant threat actor uploaded incriminating files to the laptop of Mr. Swamy.

Great to see how bulk_extractor was used to extract the NetWire C2 server communications coming from slack space in the hibernation file. Arsenal also applied memory forensics techniques on the hibernation file - identifying unique, relevant memory traces produced by NetWire and then recovering them from Mr. Swamy's hard drive.

Additionally, The Washington Post reporter, Niha Masih, shared reports with me of the investigative questions asked by the Pune police and the responses from the Regional Forensic Science Laboratory (RFSL) related to devices seized from Mr. Rona Wilson. It became clear that the digital forensic process appears to be a solely demand-driven investigation and led by the tactical investigators of the Pune Police. [1]

The RFSL should have been more critical in understanding how artifacts had been produced on the hard drive of Mr. Wilson and also defined different investigative scenarios. One such scenario could have been: Mr. Wilson’s computer had been compromised by a nation-state threat actor who uploaded incriminating documents to his system to incriminate him in a plot to murder Prime Minister Modi. By researching this type of scenario, the source of the produced artifacts should be explained, which in the case of Mr. Wilson or Mr. Swamy did not happen. If you actually put effort into finding exculpatory evidence, you’ll usually end with more robust evidence against the victim in case exculpatory evidence is not found. In this case, defining such an investigative scenario may have prevented Mr. Wilson and Mr. Swamy's long incarcerations.

By examining the RFSL report, I found the presence of an NJRAT/H-Worm backdoor on a pen drive seized from Mr. Wilson. Unfortunately, the malware was not identified as such by the RFSL. This and other findings in their report illustrate the poor quality of the digital forensic process used against the devices seized from Mr. Wilson. Although this piece of malware does not seem related to the attacker identified by Arsenal, it should have given the RFSL at least a red flag that malware was found on evidence seized from Mr. Wilson. Why did they not report this? Does the RFSL not perform anti-virus scans against seized material? Because if they did, they likely would have had waves of alerts against devices seized from the Bhima Koregaon defendants.

In many simple cases, the at-scale digital forensic process is sufficient. Still, by examining the reports of Arsenal and the RFSL, it is clear that one of the biggest threats to digital forensics is not knowing when to perform a more thorough analysis. Is your digital forensic process sufficient to determine if a nation-state threat actor has targeted a victim? Although several best practices have been published on how to perform digital forensics, many do not include performing default malware scanning against seized material nor defining different investigation scenarios, or including reference tests (simulation) to understand the behavior of certain applications and their artifacts.

[1] Disclaimer: Anchored Narratives only received screenshots of the reports of Mr. Wilson and does not have a full view of other digital forensic documents that have been produced by the Pune Police or the Regional Forensic Science Laboratory.